Are wolves to blame for the deer decline?

The Minnesota deer harvest was down across the state this season, especially in the Northeast region.

“This last season, we had about 25,000 deer killed by hunters, and that’s 21% down from the previous year and 37% below the five year average,” said Minnesota DNR Large Carnivore Specialist Dan Stark.

The lower success rate has resulted in some frustrated hunters giving up.

“We hear a lot of reports of deer camps that have been around for generations that just don’t exist anymore. Just people are unfortunately throwing in the towel on this great tradition that we have in the state,” said Minnesota Deer Hunters Association Executive Director Jared Mazurek. “That’s a big, big initiative that MDH is working on as to how we can recruit new hunters into this tradition as well as get some of those hunters that have been hunting their whole life but are just frustrated and not not really participating anymore. How can we get them back into the sport?”

In September, the Sturgeon River Chapter of the Minnesota Deer Hunters Association (MDHA) put up a billboard that placed the blame on the wolf population, stating that wolves devour over 54,000 fawns a year.

This claim has been disputed by multiple sources, including the Voyageurs Wolf Project.

“It’s not very clear where that number came from, and one of our biggest critiques on just sort of a scientific level of that number is that there’s really just not enough information to arrive at any estimate for the state of Minnesota,” said Voyageurs Wolf Project Project Lead Tom Gable. “There’s very little research done on wolf predation on deer farms, and to our knowledge, there’s really no scientific peer reviewed studies that have described the number of fawns a typical wolf kills during the summer or throughout the whole year. So how an organization could reach a number that’s supposed to represent the state sort of statewide, Wolf population is perplexing.”

The billboard was not approved by the Minnesota Deer Hunters Association due to the lack of proof behind the number. The MDHA does, however, support the intent behind the billboard.

“We need wolf management. We need management of all species for the benefit of all species,” said Mazurek. “We support the message. We want to see wolf management in the state, but we don’t know how many fawns are killed each year by wolves.”

The billboard was taken down, but the public debate continues. Hunters for Hunters is a Minnesotan group that has held several public meetings to try to solve what they believe to be the cause of the deer decline.

At a December 6 meeting in Carlton, several people spoke in front of a packed room to voice their concern.

“You guys are seeing it, right? You guys have been sending me pictures from cell cams with a wolf running a deer. First frame. 2 minutes later, here comes the wolf. The deer has zero chance of out running,” said Hunters for Hunters Board Member and Whitetail Deer Expert Steve Porter.

Federal law currently prohibits wolves from being hunted, but the legal status of hunting wolves has changed many times. The following is the timeline of changes:

- 1974: Wolves listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA)

- 1978: Wolves listed as threatened in Minnesota

- 2007: Wolves delisted

- 2008: Wolves relisted

- 2009: Wolves delisted

- 2009: Wolves relisted

- 2012: Wolves delisted

- 2014: Wolves relisted

- 2021: In January, wolves were removed from the Federal ESA.

- 2021: In February, Wisconsin quickly held a wolf season in which the 3-day season surpassed established goals by 82%. This drew fierce criticism by wolf advocates and immediate talk of legal action.

- 2022: In February, wolves were relisted on the Federal ESA.

According to Stark, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is working on a proposed rule that would assess the status and make a determination on the listing this February. If wolves were to be delisted again, the state wolf plan would be enacted. Both the MDHA and the DNR collaborated on the plan and would support delisting.

“Minnesota’s provided evidence that wolves have been recovered throughout the last couple of decades. We’ve supported delisting, and I think that wolves have recovered and should be managed under state laws,” said Stark. “The state’s in a position to manage wolves and establish a long term conservation effort to continue to support wolves and manage conflicts where they occur and make sure that we continue to have a healthy wolf population in the state.”

The Minnesota DNR administered two wolf hunting and trapping seasons in 2012-2014. The decision on whether to have a wolf hunt again will not be made until the species is delisted.

Both the DNR and Voyageurs Wolf Project believe there has not been a significant population increase as hunters claim.

“There’s wolf research going back to the 1970s and 1980s, and basically all the research that’s occurred, including our own, suggests that the area has sustained sort of a dense, stable wolf population for several decades,” explained Gable. “And stable doesn’t mean that there’s not changes through time, but it means that there’s not sort of an increasing or decreasing trend over time.

Wolves do not occur across the state. An estimated 2700 wolves occupy around 31 counties in northern Minnesota.

“The largest or highest number we ever estimated was about 3020, and that was in the early 2000s, about the same time that we had a higher, higher deer population and higher hunter success,” explained Stark.

Gable added that if the wolves were eating too many deer, it would be unlikely to see the population hold steady or increase.

“No animal can continue to persist at the same level while their food source is just plummeting. It just doesn’t happen,” Gable explained. “And they don’t just eat deer. They eat rabbits and everything else. In the summer in particular, their diets are very varied. Just because there’s a lot of different food sources, then in the wintertime, their diets get a bit narrower because they’re really going after deer at that time.”

According to the DNR, wintertime may be the most to blame for the decline in deer populations- over wolves or other predators.

“Certainly there’s been evidence that deep snow affects the survival of deer. It reduces, you know, the nutritional condition that they’re in because it’s harder to get food, harder to find or get access to food in winter months,” said Stark. “They have to expend more energy under those conditions as predation rates increase. So as snow deaths increase, we see higher rates of predation on deer from wolves. They’re taking advantage of the vulnerability that deer are in under those conditions.”

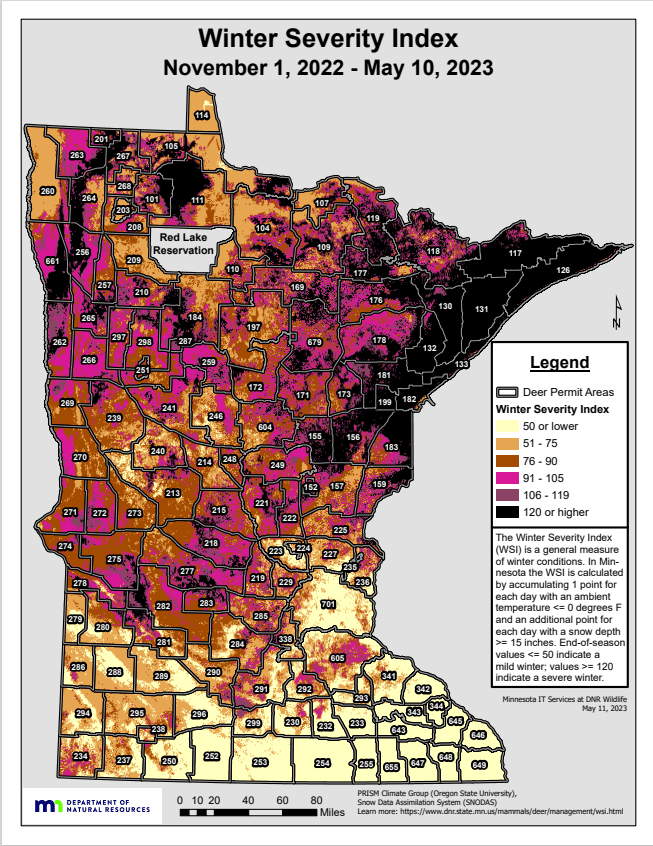

The past couple of winters saw extreme snowfall, even setting a record last year. As the Winter Severity Index (WSI) shows, the Arrowhead region had the most severe winter in the area. It was also the region with the greatest decline in hunters’ deer kills this past hunting season.

The previous snowfall record was set in 1995-96, and what happened with the deer population then could be a trend we see again.

“In the late 1990s, we had severe winters. We had a deer population that was kind of on the upswing. But following those severe winters saw a pretty drastic decline in deer numbers and hunter harvest,” Stark explained. “We don’t have a lot of control over the winter conditions, but that can have a significant influence if we have milder winters or a series of mild winters, and that was the case back in the early 2000. Deer populations rebounded relatively quickly.”

Despite having much lower wolf populations that Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan also had a decrease in deer kills by hunters this year.

Wisconsin’s deer harvest was down 19 percent from 2022- with losses even higher in the northwestern Wisconsin forest zone. Michigan had a decrease of 17 percent from 2022.