Goodbye La Niña: Tracking the transition

A change in the Pacific Ocean will soon impact weather in the Northland. For two winters, our region has been affected by a La Niña climate pattern, but we are seeing that pattern shifting. So what does this mean? The Storm Track Weather Team explains the differences between La Niña and El Niño, and how it will affect our lives.

Starting with Meteorologist Sabrina Ullman. Sabrina explains what the patterns are of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), and its phases, and how the climate pattern impacts Northland winters.

El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) describes climate patterns caused by the interaction between sea surface temperatures and surface pressures in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Changes in this portion of the ocean have a widespread effect on climate.

When ENSO is neutral or at its normal state, trade winds blow east to west, pushing warm surface waters towards Asia. In turn, deep, cool waters rise to the surface along the coast of Peru and along the equator.

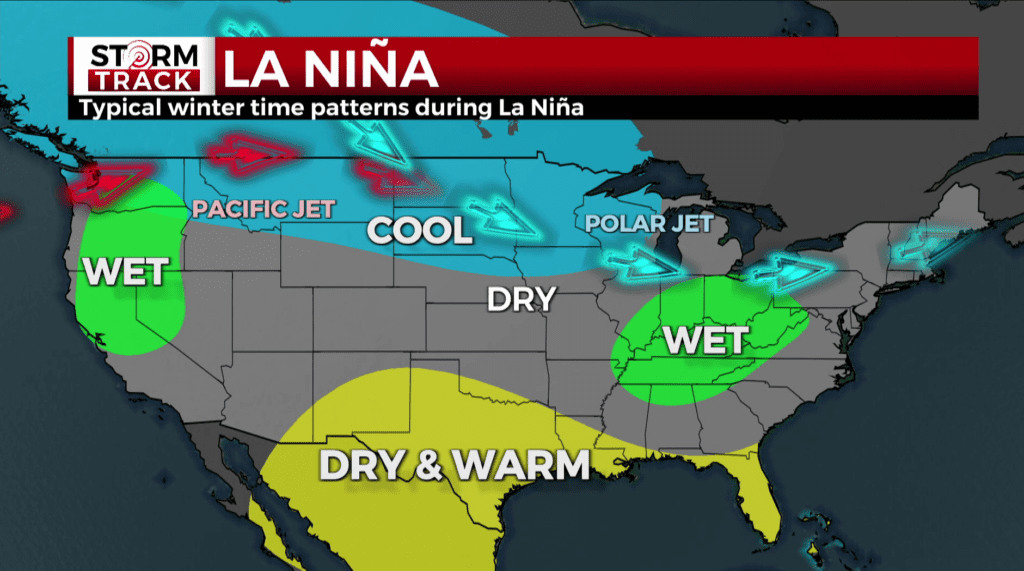

During the cold phase of ENSO, known as La Niña, the easterly trade winds are stronger than usual. This causes cooler water to surface in the eastern Pacific.

ENSO has been in the La Niña phase since July of 2020. During La Niña, the Northland tends to have cooler winters. The polar jet stream is variable, occasionally shifting to bring us more Arctic air and more snow like the last two winters.

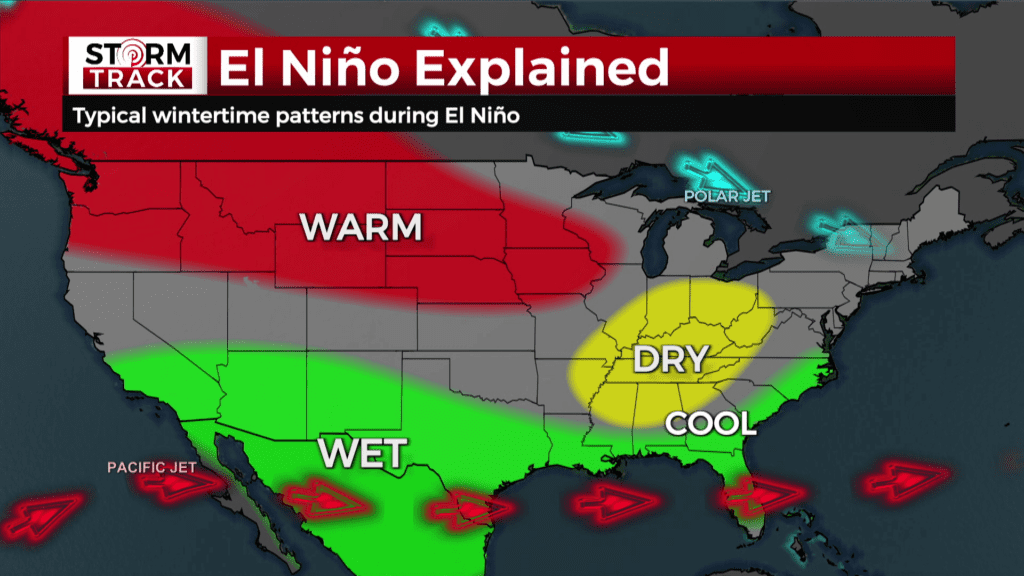

The opposite effect occurs during the warm phase of ENSO, known as El Niño. During this phase, the easterly trade winds weaken and sometimes even switch direction. This pushes warm water off the coasts of South America.

During El Niño, the polar jet is consistent and stays further north. Our area tends to have warmer winters with less snow.

The phases of ENSO flip every 2-7 years, pausing in the neutral phase in-between. The neutral phase is what we are heading toward currently. Having as long of a stretch of La Niña as the current one is rare, but similar situations have happened before.

Next, this prolonged La Niña is certainly rare, but similar situations have happened before. Meteorologist Brandon Weatherz is putting the current La Niña into historical context.

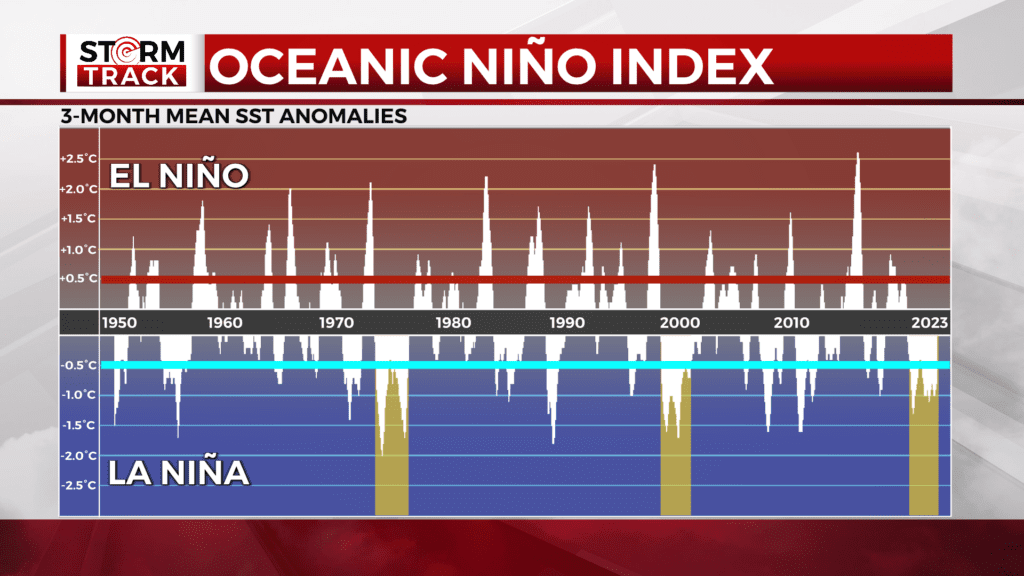

He sifted through all of the data we have on the El Niño Southern Oscillation. Brandon found two long-lived La Niñas similar to this one. One way to track ENSO is with the Oceanic Niño Index.

This plots three-month average sea surface temperature anomalies for a specific portion of the Pacific. NOAA’s record on this began at the start of 1950 and takes us to the start of 2023. Think of it as a timeline reflecting El Niños as the warm phases peaking past the red line and La Niñas as the cold phases peaking past the blue line.

WDIO Storm Track Weather Department.

The wider the set of data is, the more prolonged the event is. The current La Niña began in the summer of 2020, and has now seen us through our third winter. There have only been two other three-peat La Niña winters. One spanned the winter of 1998 to spring 2001. The other was from the winter of 1973 to spring 1976.

What gets really interesting is looking at the springs that followed these previous events. Spring 1976 in Duluth began with a cold, wet, and snowy March. April was warm and dry with nothing for snow, which is certainly below average. May ended up being the driest on record with only 0.15” of precipitation. Meanwhile, temps were relatively normal and we only a trace of snow, which is close to average.

The spring of 2001 featured a dry and less snowy March with temperatures close to average. April shaped up to be the wettest on record with a whopping 8.18” or precipitation. April’s temps and snowfall were rather normal. May was pretty run of the mill with slightly warm temps and relatively average precipitation. No snow, which isn’t far below average.

Both three-peat La Niñas were followed by springs that were noteworthy for opposite reasons. A record wet month for one, a record dry for the other.

As for what we can expect moving forward, Chief Meteorologist Justin Liles is breaking it down.

Now that we know what ENSO is, how important it is on our weather and knowing that long stretches of La Niña have happened in the Northland before, we now have to ask, what does this mean for us moving forward.

ENSO-neutral conditions are expected to begin within the next couple of months, and persist through the Northern Hemisphere this spring and early summer. As Brandon mentioned, we could go either way this spring. This year we are leaning toward a wet start in March and April, with drier conditions in May. It appears like we will be having near normal temperatures this spring.

As we head into summer, this pattern change suggests that 2023 will be warmer than 2022. In fact, it could be among the hottest years on record.

Two of the last three Northland summers have been two of the hottest summers on record. Those years, were during La Niña. With more neutral conditions expected this summer, North America will be losing its largest driver of weather as the jet stream shifts. In its place should be a more chaotic weather pattern, one that ends up being more “normal” than what we have seen during the last few years.

Since a strong jet stream is an important ingredient for severe weather, the position of the jet stream helps to determine the regions more likely to experience tornadoes. This would mean more severe weather to our south.

We will still have our fair share of storms but the more violent storms look to stay in the middle part of the country.