Reroute Controversy: Line 5 litigation

A philosophy known as ” seven generations ahead ” is deeply ingrained in the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa culture.

“We always try to look to that next generation,” explained Tribal Chairman Robert Blanchard. “My grandpa looked out for me and what I would have when I was growing up, and now I’ve got to do that for my grandchildren and they have to do it for their children and their grandchildren, until you always look out for them seven generations that are to come, so that they can live at least the way you did, if not better.”

Blanchard and others believe preservation means doing everything they can to protect the environment.

“I think our wild rice is one of the important things we fight for. It is hundreds and hundreds, if not thousands of years old. It’s been there and it’s been there as a food for us that we harvest annually,” said Blanchard.

The Bad River is used for wild rice, medicine, and fishing. Blanchard says all of these aspects are at risk.

“When I was growing up, I fished these rivers to feed my family, and in the spring of the year, we would harvest the walleye that would come upstream. And it’s right where that pipeline crosses Bad River,” said Blanchard.

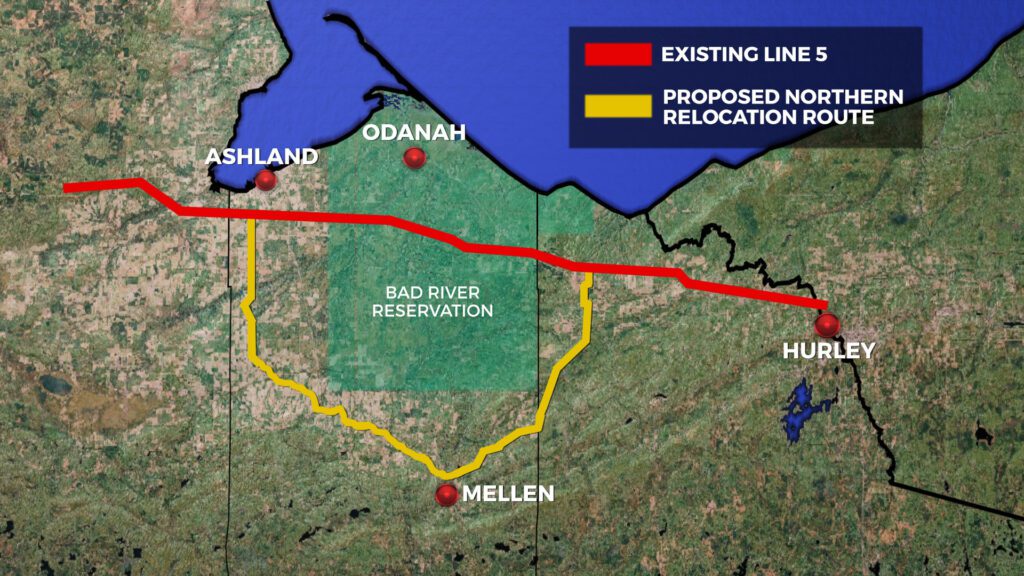

Enbridge’s Line 5 originates in Superior, runs through northern Wisconsin and Michigan, and ends in Canada. It is 645 miles long with 12 miles of it passing through the Bad River Reservation.

“Wisconsin, like Minnesota has no domestic production or reserves of petroleum. So that means the petroleum needs to be transported here,” said Enbridge Midwest Region Director of Operations Paul Eberth. “Pipelines are the safest, most efficient mode for transporting crude oil across our country.”

Line 5 was installed in 1953. Before then, Eberth says oil was shipped on tankers across Lake Superior. Since Line 5 was installed, oil shipments have been via pipeline.

Enbridge acquired easements for the area of tribal land Line 5 crosses. An easement is the right to use someone else’s land for a specified purpose. The Line 5 easements had to be renewed several times, most recently in 1992.

“I think that 1992 data is relevant to where we are now because in 1992 when we renewed easements with the band, we renewed easements that the band owned themselves for 50 years. So those continue in effect until 2043 and there’s no dispute about those easements,” explained Eberth. “And then after 1992, the band started to acquire interest in other parcels on the reservation and those parcels had an expiration date of 2013.”

The easements that expired in 2013 cover around two miles of land owned by the Bad River Band. After four years of discussion with Enbridge, the tribe passed a resolution in 2017 stating they would not be renewing interest in the rights away across the Bad River Reservation. This resolution directed the removal of the Enbridge Line 5 pipeline from tribal lands.

In 2019, the Bad River Band filed a lawsuit against Enbridge to force the decommissioning and removal of the Line 5 pipeline. A federal judge ordered that removal by 2026.

“We don’t want it in our neighborhood. We want it taken out of our watershed,” said Blanchard. “Line 5 goes right through the middle of our reservation right now, and we’re trying to get that moved off of our reservation. And then they propose to do a reroute around the borders of the reservation, which is still within the watershed of the Bad River Watershed and within suited territories of our treaty rights. All in all, if anything happens, it’s still gonna affect the things that we’ve been fighting for.”

Enbridge began working on the reroute proposal as soon as the initial lawsuit was filed.

“That works by doing survey work, you know, understanding the lay of the land, routing it in a way that has the least amount of impacts both environmentally and to landowners,” explained Eberth. “We also sought landowners that were amenable to having the pipeline and the property. So we were able to acquire easements voluntarily. So there will be no condemnation needed of any land along the 41-mile relocation project.”

With an established survey corridor and a proposed reroute, Enbridge submitted its application to the Wisconsin DNR in 2020.

Permits were issued four years later, prompting a lawsuit from the Bad River Band. The tribe is asking an Ashland County judge to stay the Wisconsin DNR’s environmental impact statement for the reroute proposal and reverse state construction permits. Additionally, several groups, including the Bad River Band, petitioned the court to demand a hearing on the DNR’s approvals. The Sierra Club, the League of Women Voters, and Clean Wisconsin all want an explanation of the approval.

Staff Attorney Evan Feinauer says a contested case hearing would get a judge to take a second look at DNR determinations. Clean Wisconsin’s stance is that the current reroute plans are unlikely to succeed without causing illegal impacts to the environment.

“We’ve been studying this proposal, and its impacts on the environment for years now,” said Feinauer. “State statute prohibits anyone from doing anything that’s going to say fill a wetland if the net result at the end of the day is going to be causing significant adverse impacts to wetlands, and we think this is going to.”

Feinauer added that based on the standard of the law, a stay is needed in this case because you cannot un-fill a wetland.

“If Enbridge were to get out there and start doing significant damage to the environment only to ultimately lose the case, there’s nothing they could do to put it back,” said Feinauer.

Eberth says in addition to Enbridge having inspectors on-site during construction, the state will have its own inspectors there to make sure everything is done properly.

“The first plan of attack is to ensure that, you know, if something’s being done improperly it gets corrected right away, either by us or by the government. Either by us or by the state’s inspectors. We’re required to abide by the law, just like any other business,” said Eberth.

Clean Wisconsin’s stance is that Enbridge will not be successful in limiting environmental impacts.

“I mean, we’re talking about dredging, blasting the bedrock, removing tons of vegetation, including permanent maintenance along the corridor. This is a big, big thing they’re doing to the environment,” emphasized Feinauer. “They’re understating the harm that’s going to cause, and then they’re overstating their ability to kind of put it back together again when they’re done. Their plans are very confident that they’re going to be able to restore this area to the way it looked and the way it functioned before construction, which is- overly ambitious is a sort of an understatement.”

Enbridge disagrees, saying they have several permit conditions to follow and that no matter where it goes, the pipeline will operate across various watersheds.

“The designs specifically to the relocation project, for example, many of the crossings of streams will be done with a trenchless method. So directional drilling so that there isn’t any digging or trenching across streams,” said Eberth. “That helps protect against any impacts to fisheries. So that’s just one way on the relocation project we’re working to ensure that the resources are protected.”

Adding to the environmental concern is a recent oil spill not far from home. Enbridge’s Line 6 spilled 70,000 gallons of oil in Wisconsin this past November. The spill was about 60 miles west of Milwaukee.

RELATED: Enbridge pipeline spills 70,000 gallons of oil in Wisconsin

“The facilities that we have in place to keep the environment and people safe worked. The release was not acceptable. Don’t get me wrong, but the release happened on Enbridge property,” said Eberth. “It didn’t go off our property. It didn’t impact any streams or wetlands. It didn’t impact any people.”

Clean Wisconsin’s Attorney says the Line 5 relocation proposal does not meet the legal standards, and the risk of an oil spill exacerbates the situation. This leads to more questions about the risk involved.

“This is a company that operates a lot of these pipelines,” said Feinauer. “They’ve represented to DNR that the risk of an oil spill from the new section of Line 5 would be astronomically small. We’ve been dubious about that assertion. We think it’s, again, probably overly optimistic about their ability to avoid these kinds of problems.”

But what’s the alternative to a pipeline? According to Enbridge, Line 5 moves about 540,000 barrels of oil a day.

“That’s more than all of the residents here in Wisconsin consume daily. If there’s no Line 5, the product needs to move through other modes of transportation. Those other modes of transportation, for the most part, bring higher emissions and higher costs. And in some cases are more risky, such as, you know, be a truck delivery,” asserted Eberth.

Eberth highlighted an example of North Dakota not having enough pipeline capacity only about a decade ago.

“The rail lines were congested to the point where grain from farmers, you know, they couldn’t get grain onto the rail and grain couldn’t get to market. So those are the types of impacts that happen when the transportation infrastructures are insufficient,” explained Eberth.

The current lawsuit could go as high as the Supreme Court as both sides keep fighting.

“We’re going to keep swinging back because we’ve got seven generations ahead of us that we have to think about,” said Blanchard.

Enbridge says the project will “generate millions of dollars in construction spending for local communities, create over 700 family-supporting union jobs, and preserve the flow of essential energy that millions of consumers in the region rely on every day.” The company has committed to spending $46 million to work with native-owned businesses and hire tribal members if the reroute goes through as planned.